Review of Afghanistan developments

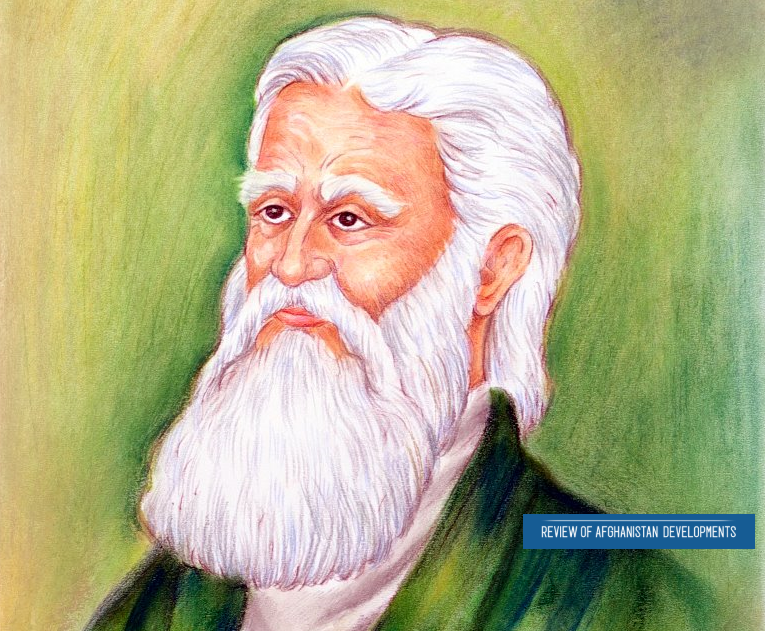

Biography of Rahman Baba

Rahman Baba, born Abdul Rahman Momand (1663–1749), is regarded as one of Afghanistan’s most distinguished poets and a significant influence in the Pashto language. Although there are varying reports, Peshawar is frequently mentioned as his place of birth.

Rahman Baba received an education that encompassed the Quran, Hadith, jurisprudence, literature, and mystical writings. There is a lack of consensus regarding the precise year of his death, as well as the year of his birth. Currently, his tomb located in Peshawar stands as one of the most significant cultural and spiritual pilgrimage destinations in the area. Overall, comprehensive information about the life and biography of this Pashto-speaking poet is not fully available; however, his literary works reflect his personal and intellectual heritage.

Rahman Baba’s collection of poetry

Rahman Baba’s Divan comprises approximately five thousand verses and is divided into two distinct books. Each book is self-contained regarding its lines and features ghazals, qasayds, and makhmas that convey moral, mystical, human, social, and religious themes through language that is both simple and profound. The clarity and eloquence of his expression have rendered Rahman Baba’s Divan one of the most cherished poetic works among the Pashtun people, establishing his unique standing in the literary world.

Both volumes exhibit a harmonious quality and are comparable in their use of poetic techniques, the subtlety of imagination, and the precision of imagery. His poetry is enthusiastically embraced within the popular, religious, and cultural spheres of the Pashtun community. The diwan of this Afghan poet is rich with themes of knowledge, Sufism, democracy, and philanthropy, holding significant literary and moral value not only for the Pashtuns but also for those outside this ethnic group. A notable illustration of his straightforward yet profound style can be found in this part of ghazal:

Translation:

Plant flowers, that your land may turn to a garden fair;

Sow no thorns, for in your own feet shall sprout the thorn’s snare.

Translation:

When you let fly an arrow toward another’s heart, beware —

for that same shaft, one day, shall seek your own breast to impair.

Translation:

When you dig a pit for another, mark this well and true —

the path you walk may one day pass where that pit gapes for you.

These verses demonstrate how Rahman Baba, using straightforward and gentle language, conveys profound moral and human messages; a message focused on love, loyalty, goodness, the avoidance of harm to others, and an understanding of the truth regarding human behavior. Similar to a clear mirror, his poetry compels the reader to contemplate their own actions and reveals a pathway that transcends personal morality towards a flourishing social existence.

Rahman Baba and the Persian language

During Rahman’s time, Persian served as the language of science, mysticism, and administration. While Rahman Baba wrote his poetry in Pashto, the essence and form of his work resemble Persian, and he conveyed numerous mystical and ethical ideas from Persian into Pashto. Besides Pashto, he was also skilled in both Persian and Arabic.

Rahman Baba’s literary creations are profoundly shaped by the influential Persian poets, including Saadi Shirazi, Hafez Shirazi, Sana’i, and Rumi.

Rahman Baba and Hafez Shirazi share notable similarities in various aspects: both are esteemed ghazal poets, there is a lack of detailed information regarding their early lives, and both possess independent divans. Their poetry is often utilized by individuals seeking fortunes. Consequently, both poets are referred to as the “tongues of the unseen”. In light of the principles of prosody and badi’ah, which encompass the art of welcoming, assuring, and drawing inspiration, instances of poetic parallels between Rahman Baba and Khwaja Shirazi are highlighted here.

Hafez:

By the alchemy of your affection, my face turned to gold;

Yes, by the grace of your kindness, even dust becomes gold.

Rahman Baba:

What turned my soil like cheeks to gold was not mere amorous art —

It was, within my own heart, the alchemist’s part.

Hafez:

Rose in embrace, wine in hand, and the beloved mine at last —

Though monarch of the world, on such a day, I am a slave to this moment vast.

Rahman Baba:

With love in my heart and the wine cup in my hand today,

The throne of this world is but a slave to my sway.

Hafez:

O Cupbearer, do not postpone today’s joy to tomorrow’s day,

Or bring me from Fate’s court a writ of reprieve, I pray.

Rahman Baba:

Why offer lengthening vows, one tomorrow on another strung?

Bring me instead a letter of reprieve, from fate’s court unsung.

Hafez:

My aim from mosque and tavern is union with You alone —

I hold no other thought, God is my witness, this I own.

Rahman Baba:

Wherever I go on pilgrimage, my purpose is but one (You):

I am a pilgrim of the tavern and the shrine, in truth, as none.

Hafez:

The world’s affairs could never draw my heed or care aside,

till your face, in my sight, with such beauty did reside.

Rahman Baba:

Those wayfarers who contemplate the world’s endless view,

From this world, they seek but the One who makes all worlds anew.

Hafez

The rapture of love is not in your head,

Go, for you are drunk on the wine of the grape instead.

Rahman Baba

Rahman’s wine is born of love alone,

Not from the grape, nor from the vine it’s grown.

Rahman Baba’s poetic style

One of the outstanding features of Rahman Baba‘s poetry is his ability to express deep and philosophical concepts in simple and understandable language. With this simplicity, he invites man to reflect, self-knowledge and self-purification. His poetry is a mirror of human innate feelings and a reflection of the culture and spirit of the Pashtun people; he speaks in a soft and unadorned language about social life, etiquette, morality and mysticism. Rahman considers love to be the driving force of the world and on that basis draws a framework for human life.

An example of Rahman Baba’s poetic theme:

1- About true love:

Translation:

Who love, yet leave the Divine apart,

Plant love with neither root nor heart.

Translation:

Love empty of the Divine is only sorrow for the soul;

Who binds their heart to other than God, shall never be whole.

Translation:

What folly, to fix the heart on other than the All-Encompassing Face!

The self-opinioned who cherish their own opinion, are bereft of grace.

2- About faultfinding and introspection

Translation:

When you forever fix your gaze upon the flaws of another’s soul,

Why stay heedless of the faults within you, known to God, your whole?

Translation:

If you spot a speck of fault in another’s soul,

You swell that speck into a mountain, whole.

Translation:

God granted you the rank that angels hold in grace,

But with your acts, you make your soul an ox or donkey in place.

3- Concerning the prospects of life and the urgency of taking action

Translation:

You have no second coming to this world’s fleeting span;

Today is your turn — speak truth, or falsehood, as you can.

Translation:

Whatever passes beyond its appointed hour becomes a Simorgh, rare —

The Simorgh is never trapped within the snare.

Translation:

If you have an aim, hasten — for time is brief and fleet;

Do not be deceived by this life’s fleeting, false seat.

Despite being a Sufi poet who steers clear of worldly impurities, Rahman Baba’s poetry is imbued with the essence of life. He does not merely urge individuals towards monasticism; rather, he instructs them on “how to live.” In his perspective, only genuine love holds significance, while other advantages, such as ethnic and social privileges, are deemed inconsequential. Rahman regards stability, a pure heart, and sincere actions as the essential foundations of life, directing individuals towards simplicity, justice, gratitude, and divine love.

Rahman Baba’s Embrace of Ethnic and Religious Tolerance

One of the remarkable intellectual traits of Rahman Baba is his tolerance. He did not view ethnicity and religion as measures of worth, instead regarding humanity as paramount. He held the belief that:

Translation:

Tribe and lineage matter not — a pure heart alone is prized;

Every human is a human, and all are brothers recognized.

There is also contention regarding his tribal affiliation; while some have regarded him as belonging to the Momand tribe, the poet himself refutes any tribal connection in certain verses and presents a romantic and mystical identity as the core of his being:

Translation:

I am a lover — all my being and affairs are with Love alone;

I am no Khilji, nor Dawudzai, nor Momand — I am love’s own.

Related Aticles:

Aisha Durrani: A look at the poetry of An Afghan Woman

Khushal Khan Khattak; Pashto-language poet

Conclusion

Rahman Baba, through his straightforward language and deep insights, conveyed a message encompassing love, ethics, mysticism, and humanity. He is a poet who surpasses the limitations of ethnicity, faith, and time, urging individuals towards purity of heart, kindness, justice, and divine love. His writings demonstrate that Rahman Baba serves as an exemplary figure for humanity, philanthropy, mutual acceptance, altruism, and dignified living; a paradigm that could inspire both personal and communal lives of all Afghans in the present day.